Interview with New Media artist Daniel Temkin on Esolangs

past_events

admin@codework:~$ sudo codework

CodeWork member, Chris Lindgren, interviews New Media artist Daniel Temkin. They discuss esolangs, or esoteric programming languages, Temkin's particular esolang projects, the esolang community, and intersections between programming and human languages.

admin@codework:~$ ▊

Interview with New Media artist Daniel Temkin on Esolangs

New Media artist Daniel Temkin discusses esolangs, or esoteric programming languages, his particular esolang projects, the esolang community, and intersections between programming and human languages.

Esolang Interviewee

-

Daniel Temkin | New Media, Art, Esolangs

Daniel Temkin is a new media artist with a diverse portfolio that explores the intersections between algorithms and interfaces, understanding and obfuscation, and the aesthetic outputs that course all --> throughout --> his --> codework. One of his more recent projects, Esoteric.codes, is the focus of this interview.

Interview transcript with Daniel Temkin

The CodeWork team is thrilled and honored to present this interview between CodeWork member, Chris Lindgren, and new media artist, Daniel Temkin.

Please feel free to share this interview (#codework). You can contact either Chris (@lndgrn) or Daniel (@rottytooth) on Twitter.

Lindgren: For those of us who are unaware, could you sum up esolangs / esoteric programming languages? What are they in the scope of this term we've constructed "code-work"? Maybe you could talk about your first experiences with them, what esolangs you've developed, and why you found them compelling.

Temkin: Sure. Esolangs (from "esoteric programming languages") are languages designed for anything apart from practical computing; experiments with programming concepts, conceptual pieces that explore the edges of what a programming language can be, or experiential works one participates in by programming in them. Ordinarily, programming languages are designed for clarity. Esolangs are not like this, they have logic so strange it takes significant work to understand or a vocabulary that does the same (or very often, both). They are related to concepts like Obfuscated Code, which similarly makes language visible, and constrained programming such as Code Golf.

I'm not sure when/how I first came across esolangs, but I remember being drawn to brainfuck, Whitespace, and Piet early on. I loved the idea of expressing an entire Turing Complete language in just eight commands (all punctuation marks) in brainfuck, or using the space between words in, say, a C program to write a hidden Whitespace program. Piet went one step further, encoding commands into pixel color in an image. The first esolang I wrote, velato, began as a "Piet for music:" a language where code is read as MIDI files. The programmer/composer writes songs structured by the rules of the Velato language. I was curious what kind of music would result. I've experimented with similar ideas in Light Pattern, which uses photographs as code. Since I'm more comfortable with photography than music, I was able to go further in experimenting with Light Pattern programs, developing series of works that tie the behavior of working programs to the images used to code them in LP. One example is my Unmaking series, where I photograph a performance or other visual work based on text, transforming it back into its source text by changing the color and exposure of each frame. An example is this work based on George Brecht's Three Lamp Events. His piece concerns turning on and off lamps as a performance – I turn on and off lamps (and photograph them at varying exposures) in such a way to create the correct color and exposure settings (as called for in the Light Pattern language) to generate his original score. I have a Yoko Ono piece that I never completed; I broke a camera trying. :) Like a Fluxus score, one can choose to actually carry out the instructions, but it can sometimes be understood by its instructions alone. This is true as well for the rules that make up a programming language – they are both primarily dematerialized forms.

Lindgren: How do you approach the process to design an esolang? What are your own particular goals in doing so?

Temkin: Esolangs begin for me with a specific question or idea I want to explore. I came up with the idea of my Entropy language sitting in a long meeting with programmers that turned to coding standards. I had been thinking about how programming (and computers more generally, to some degree) encourages a sense of compulsiveness – minor mistakes can cause your code not to run and yet know that you'll never get it exactly right, bugs are inevitable. If you're thinking this way all day, it's easy to carry that logic to other situations where it will be less useful: both the false objectivity that sometimes very smart programmers have, and the compulsiveness of wanting things done in a very specific way (like some overly eager coding standards). With Entropy, I wanted a language that would force programmers to get it wrong, to approximate, to write something that could never work exactly the way they want. In Entropy, all data decays the more it's used, giving programmers a short window of time to get an idea across before their data turns to mush.

Lindgren: I love this: creating an esolang to illuminate the ways programming practices and habits bleed into situations beyond the scope of their efficacy. I also really appreciate this notion of "data decay," because I often get the (broad) sense that there's a cultural myth about data as some monolithic, long-lasting, durable thing. Yet, all data needs to be packaged and interpreted and is quite susceptible to the quick changes in software environments. (I'm thinking about Rosa Menkman's "A vernacular of file formats" and Vint Cerf's idea of "digital vellum).

These are just some of my responses to this constraint in Entropy, but could you speak to some of your own reasons for this concept of "data decay" as a more salient aspect to a programming language?

Temkin: At the time I was writing Entropy (2011), I was also experimenting in the glitch style, so there is certainly some overlap there. While Entropy uses data decay primarily to take control out of the hands of the programmer, this approach grounds data, taking away the sense of something ethereal and eternal. In a sense, it connects to the brand of glitch rooted in digital materialism (which I believe Vernacular to be), emphasizing data as something which not only can degrade, but has a channel or medium its own qualities and behaviors that become more apparent around the pure signal we are attempting to decode.

Entropy does not corrupt data when it is first written; as long as you never read or update that data, it will stay as written.* It is only when data is accessed that there's a chance it will go "off." So data becomes a limited resource; at first, the data might change slightly, then slightly more; it's a risk each time it's used. To make Entropy accessible to non-programmers, I re-wrote the classic Eliza program (the original chatbot from 1966) in the language, and ended up with Drunk Eliza; each time she repeats one of her stock phrases, it goes a little bit more off, with random letters reducing the readability of the message. Her name, too, changes from DRUNK ELIZA to perhaps DRQOK ELIZA to DSPOK ELIYB and so on, becoming less and less recognizable. As the text mutates, the channel essentially becomes noisier, both making us more aware of the system we're partaking in and making us guess at what it is Eliza wants to tell us (by then end, only by remembering previous repetitions of essentially nonsensical phrases back to the pure "signal" as they began). One interesting thing which came out of having this online was how people talk to Drunk Eliza – they no longer care about hitting wrong keys, typing with their fists by the end, in a drunken typing style.

In Entropy, none of the corruption is permanent; by restarting the program, we get clean data and a new path of corruption. But in glitch, as a general rule, corruption is not permanent either: as Hugh Manon and I discuss in Notes on Glitch, the damage in glitchwork is simulated: erasure puts little at risk when a back-up is assumed by default.

Going back to the original question about esolang design, my other languages began similarly. Folders was inspired by the Whitespace language. Whitespace's immateriality was compelling for me because esolangs are essentially nothing but rulesets – they are their description, not a particular implementation. I wondered what is more empty than a (seemingly) blank file? My answer was a folder holding nothing but other empty folders; folders, after all, are there to organize files; I liked the idea of filling a hard drive with empty folders. I decided to encode the language into the folder structures and names, and create a language with no files. I began Time Out thinking about the order lines of code are executed; I wanted to try something different and actually offset the action of the code into the space between the lines of code – you can't put code in between those spaces (or they would just become new lines of code). Instead, I made a language where every command tells the interpreter to wait, and it's between those periods of waiting that code actually executes, based on how much time has passed. I wrote Time Out to run on the Web, and quickly realized that if you're not running it in an active tab, it can fall behind, meaning the length of time out you intended might not be what occurs, causing the wrong command to fire. So you're forced to sit and wait for your program to run, without switching tabs or starting other programs that might slow it down. If Folders is the essence of Windows, Time Out connects to the Web experience, especially calling back to the early Web.

Once I have an idea, I sketch out possible commands and imagine some sample programs. Once I've done this for quite a while, I'll start actually coding a compiler or interpreter. This is a slow process for me, so I like to have as much in place by then as possible and not risk having to start over (although that sometimes happens).

* Apart from being subjected to the same issues all data is, as you implied in the question

Lindgren: That makes sense to me as a writing and literacy scholar. Programming languages, like human languages, develop over periods of time based on what people perceive as necessary to communicate ideas linked to some sort of shared / desired action. As a rhetorician, too, I'm fascinated by how languages also have persuasive components, dimensions, or grooves that get bent and broken and revived over a culture's history. If I pressed you to identify some of those rhetorical "grooves" of one of your esolangs, what might they be?

Temkin: It's been interesting to look back over esolangs and see how some languages took certain design decisions or impulses that were tangential to an earlier language and went really far with it. Basically, esolangs began with the language FALSE in 1993. Before then was INTERCAL (which is twenty years older), but the most influential early 90s esolangers were unaware of it, so I see FALSE as having launched the movement. FALSE is a very tiny language by Wouter van Oortmerssen, who also designed practical languages like the widely used Amiga E. He was working at a time when it was more common for people to write their own software, and nearly everything on the machine was a place to intervene for programmer-hobbyists (a point that came up in the Chris Pressey interview). Amiga E was created by Wouter with no institutional support, but was a popular language in the 90s for writing Amiga software. With FALSE, he adapted Forth, a mainstream language but a very odd one (stack-oriented language). His goal was to make as small a language as possible: Forth was ideal for this; also, all the commands are single letters, which helped with the size, but also became a common feature of esolangs. Brainfuck was an answer to FALSE: fully Turing Complete but much smaller language (with only has eight commands), if much harder to program in. Chris Pressey's answer to FALSE was Befunge, designed to be the most difficult language for a compiler to understand. Ben Olmstead's answer to brainfuck and Befunge was Malbolge, the most difficult language for a person to actually write code in. Each issue which was raised by an esolang seemed to inspire a different approach to the same problem, or a different, related problem which went in a completely opposite direction.

Brainfuck is an important language for me as well. Part of its beauty is its simplicity; a tiny language, one which does little to reduce the complexity of assembly code. For me, that was the key thing; since it refuses to simplify the exchange between human thought and computer logic, I see it as dramatizing this collision. It exposes the strange logic sitting behind programming languages, an alien language belonging more to the machine than to us, and with a seemingly irrational sensibility, even though it is simple and logical as well. I wrote about this in my paper on brainfuck for Media-N Journal, and the language continues to be an inspiration for a lot of my esolang work.

Another language which I think underscores this well is Piet. Piet was probably directly influenced by Chris Pressey's Befunge. Befunge is a 2D language; lines of code can run up and down the page, backwards, etc. However, it is still written in text (with single letter commands, like FALSE). Piet, as I mentioned earlier, encodes commands in the changing color of pixels in an image; special commands tell the interpreter to read in a different direction (corresponding to Befunge commands): it starts reading left to right, but you can tell it to turn and read down and then loop back over itself. While traditional languages try to make the code understandable, to make the language transparent so that our attention falls to the behavior of the code, esolangs create a distance between the code and its behavior, between the person reading the code and the machine executing it. Piet's images have a meaning for us purely as they appear, yet are structured by their function, by the program they execute when run. Translating from one to the other is not always easy.

Lindgren: Do you think esolangs and esolangers share any of the same aims, goals, and values as more traditional approaches to computing and programming? Why or why not?

Temkin: The inclination to take something apart and experiment with its pieces, approach it from odd or unintended angles, is a key part of programming. Esolangs are different from other types of coding mainly in that they don't serve practical purposes, so are free to explore any "what if" scenario all the way through, and find approaches or make equivalences that have little hope of serving a practical need. I think the humor of esolangs is more of a programmers' humor than of, say, most digital art (Discordianism, My Little Pony, etc etc). Its culture is one of programmers, but it can only exist when you get away from aims and goals we usually have for programming languages. I think of it as art by and for programmers that sometimes makes sense to other people, but certainly not always (for example, a language like Checkout).

Lindgren: That's an interesting tension between a culture of programmers and breaking away from the dominant cultural values and aims of the culture. In the way you describe esolangers as not "serv[ing] practical approaches," I wonder what you might think of the idea that esolang practices and experimentation has the potential to communicate beneficial and "useful" criticisms, histories, commentaries to the broader software development culture; particularly by taking up the practice.

Put another way, let me compare cultures within new media art. I'm thinking about the broader conceptualization of new media art and the opinions, meanings, and messages within this trajectory. Along comes glitch and its momentum carried into the 2000s. I've heard opinions by some new media artists that they could care less about glitch art, because it's just breaking stuff. Then, they often base this claim on the assumption that they are the only one's interested in creating things that "work." This, to me, seems like such an oversight about what values, ideas, aesthetics, etc. can be experienced and made by making things that don't "work."

Sorry for the long-winded preamble, but what do you do with and about this cultural tension?

Temkin: Yes, I think having something not function "properly" is a way to make people ask – okay, what is really going on here, what is this trying to draw my attention to? There's a group of esolangs that are very technical – such as Unlambda (whose experiment is "what would a lambda-calculus be like with no lambdas?"). These are the most insidery languages, ones whose aesthetic is quite difficult to grasp for nonprogrammers, and might not even look esolangy until one starts working in them. FRACTRAN, one of the most beautiful languages IMO is perhaps one of these, although it's not really that intimidating if you're willing to think through it. It will be interesting to see if, in a generation or so, programming becomes a common enough skill that inventing languages for fun would be a common thing.

Do esolangs have to be "impractical?" I would love to see Microsoft release an official .NET version of FiM++ and we could have countless programmers writing systems code in a My Little Pony related script. I think device drivers would be far more interesting if they also related details of Twighlight Sparkle's adventures. But FiM++ is fundamentally impractical in that it makes code do something other than clearly reveal its behavior. So it is hard for me to imagine a completely practical esolang; esolangs either have logic that is strange and difficult (Unlambda) or codes that take us away from clear reading (FiM++).

The closest thing to a practical esolang would be the hobbyist languages I mentioned earlier (Amiga E and other homespun code), but some of these actually became widely used. I see the esolangs which do have a subversive stance coming from a similar perspective of glitch: the place for hobbyists to build their own languages is outside the corporate sphere, for most of us. We can build our own tools, but where there once was a place for hobbyist work in this area, mostly what we have now is only a place to make languages that offer something entirely different than what is produced by Sun or Microsoft or whoever. And it will mostly be ridiculous; not something practical, as practical languages will rarely have that same reach. INTERCAL, generally considered the first language, was a parody of languages of its time. I wrote about Checkout recently in terms of Kittler's Protected Mode (I don't believe Checkout to be intended politically, but it plays out a scenario that is similar to what Kittler wrote about, a re-claiming of power we have given up to the people who make the hardware we run code on) . There is an anti-corporate flavor to many other languages, such as some of the bizarre variations of Java and of Microsoft's languages at http://p-nand-q.com/programming/languages/index.html.

Lindgren: In a recent interview with esolanger, Scott Feeney, you asked him the following question: "It’s interesting that a number of esolangers I’ve talked to describe themselves as having been hobbyists, or “not mature programmers” at the time they were writing esolangs. Is creating a language technically complex?" What's your response to this question? And why do you think many seem to identify themselves in this way?

Temkin: My impression is that the community is not as small or tight as it was when Feeney was highly involved; that now it's more distributed, that many more programmers are aware of esolangs. Since the beginning of the Web, programmers have posted interesting side projects, sometimes developed to learn new programming skills, and esolangs are now a part of that culture. Compilers can be hard to write, which partially explains why there are so many brainfuck clones (where the punctuation marks are replaced by symbols like "blub" or "Ook" – okay, those are two that I like but it's getting out of hand now that there are dozens of them). It's easy to write a clone, you take an existing interpreter and swap out the symbols.

Writing a unique compiler for a (non-derivative) language can be a challenge, but this is part of the draw to esolangs, part of what makes it a fun from a hobbyist standpoint. I've been hoping to find or put together tutorials to help people write their first interpreter (there are a few out there, but none that I love). If someone has an amazing idea for a language but can't write the interpreter, the language is the rules – it can be posted to esolangs.org as an unimplemented language until you find a way to make it functional – or maybe someone else will find it and decide to put it into practice.

Lindgren: I understand (thanks to your blog: esoteric.codes) that there's a welcoming esolang community on and offline. I'm curious if you could speak to what kinds of values you think this community adheres to and cultivates through your code-work. And, (how) do you see these values shaping the kinds of project you create?

Temkin: Although we can understand an esolang by reading its list of rules, most are experienced better by actually programming in it (there are exceptions – perhaps Malboge, or all the uncomputable esolangs). This makes it an inherently collaborative form, so one that will thrive only if there's a group of people interested in esolangs – even if, as I suggest in the previous answer, it's a larger, less distributed community now... You mentioned the Scott Feeney interview previously – there, he emphasizes the importance of esoprogramming in terms of esolangs asking questions that one attempts to solve through esoprograms: actually writing programs in that language. Esolangs are open forms: others contribute to it, not only by exploring it through writing code, but often extending the idea: creating variations, or derivative languages.

Two of my languages, Velato and Entropy, were adapted by others for the Web. A version of Entropy was built by Andrew Hoyer – it takes the central idea of Entropy, that data should decay over time, but jettisonned the syntax and style in favor of a JavaScript implementation. The original version of Entropy has only a Windows compiler – more people experienced it through code I wrote in Entropy myself (especially Drunk Eliza) or in reading the description, than coding in it. I think Drunk Eliza gets an experience of Entropy across, but it's a controlled experience, much different than actually writing your own code in it where you can experiment and go any direction you want. With Andrew's version, it's much easier to get started writing Entropy right away, and since it's Web-based, it can be used for graphic manipulation and the like. But when he decided to come up with his version, there was little of the baggage that comes along with, say, adapting someone else's art piece. He understood my intent for Entropy, and used the concept plus the best bits of the language, there was no need to faithfully translate every command. Feeney has said that perhaps this type of collaboration is due to there being less at stake in esolangs. That's probably true, there's still little fame in coming up with an awesome language. But I think it also is tied to open source values familiar from programming – the way people show respect is different.

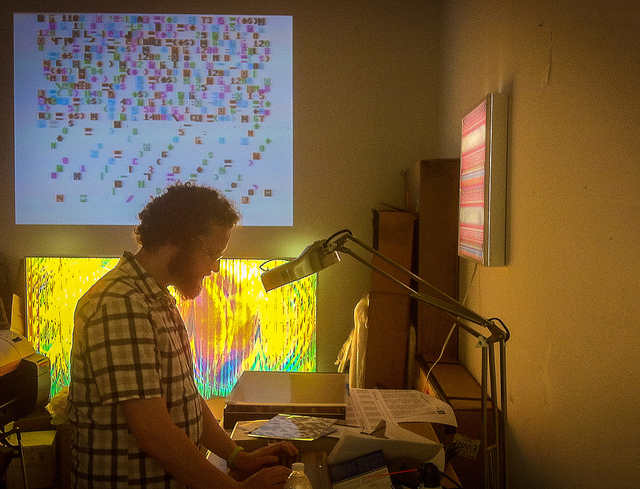

Lindgren: I remember attending GLI.TC/H 2112 and taking part in your working group (ouLANGltchpo) on esoteric languages. At one point, all of us discussed and played around with the fuzzy boundaries between human and "machinic" languages. What overlaps do you see between human and programming languages? And, how do you see studying and creating esolangs as a way to gain insight to such relationships between the two?

Temkin: Yes, one of the things I find most compelling about esolangs is that confrontation between human thinking and computer logic. In my paper on brainfuck, I looked at the spare, minimalist language as intentionally "refusing to ease the boundary between human expression and assembly code and thereby taking us on a ludicrous journey of logic." We're forced to think in terms closer to the machine, and to construct lengthy algorithms for simple tasks. For example, since brainfuck doesn't have a built-in way of representing numbers greater than one, each programmer finds their own algorithm to arrive at the number 36, perhaps jumping down in increments from 256, or multiplying 6 by itself (keep in mind, each of these are represented by strings of punctuation). What appears short and elegant in code take longer to run, so the way someone decides to represent this simple number becomes a matter of personal style. But this complexity arises not through an artificial system, but rather because brainfuck offers a smaller selection of the assembly-level commands all programming languages are reduced to in compilation -- this is one approach to dramatizing the conflict with machine logic, by taking away niceties most languages have.

In programming, we tell the machine to do specific things: it is denotative and commanding (even in "non-imperative languages"), with little room for ambiguity, at least in how the machine will interpret it. We might think of traditional programming languages as transparent, trying to make the logic of the program clear -- esolangs bring our attention to the code itself as a text, either through the difficulty of decoding the language, or through its humor, or odd sensibility. I'm reminded of your recent codeworks panel with Cristina Lopes, where she brought up her "passive aggressive" program, from her wonderful "Exercises in Programming Style" book. There's also a tantrum style, which is expressed through code behavior (essentially it refuses to run when it hits unexpected input). But just to make a point about traditional programming style vs. esolanging, there's nothing tantrum-like in the concrete language of the code: no "fuckYou" variable, it isn't formatted looking like someone hit all the keys in frustration, etc. She uses Python, which, like nearly all traditional languages, is designed for clarity, to help us see the algorithm, not the code. Esolangs are not transparent in this way, they emphasize the code as a text: either by forcing us to navigate their very odd rules, or by creating space between code and its behavior through strange vocabularies (such as the strings of punctuation that make up brainfuck). This feels somewhat familiar from the ouLANGltchpo sessions, where we played with written language, using strange systems to make language more visible as a force (as Curt [Cloninger] might put it).

In terms of mixing human language and programming langauges, some esolangers have experimented with vocabularies that are suggestive of other systems. For example, Chef features code written as recipes (that some people have actually baked, and Shakespeare reads as stage directions and lines of dialogue -- appear to be about subjects entirely different from what the code is actually doing, and bringing in concerns that add aspects to the code that have little to do with their actual machinic behavior. My first experiment with Light Pattern were simple shots of peoples' faces -- their expressions in front of the camera brought bodily gesture and nuance quite literally into the code. So this is another strategy for experimentation between human and machinic language.

Lindgren: What advice would you give someone who is interested in experimenting or creating an esolang?

Temkin: A great first step is to write out a language description. What is the idea your language is exploring, what question is it asking? I like Chris Pressey's intros for his languages (a list of them can be found here), which are very succinct. Keep this language premise in mind as you begin to define its vocabulary and rules. It will likely change/evolve as you experiment, but it's good to update it as you go, so that you don't include language features that weaken or distract from it.

I generally encourage implementation in JavaScript; once complete, it will be easier for people on all different platforms to use and extend. Sometimes there are practical or conceptual issues with JS. An example is my language Folders, which is "about" the Windows file system and only makes sense in a Windows environment – do what makes sense for the language.

A nice tool for working out ideas in JS is peg.js -- you can model a grammar on the <a href=” http://pegjs.org”>pegjs.org website. If you want to write your own lexer and parser, a basic intro can be found here. If this is all a bit overwhelming, many esolangers write implementations of existing languages before trying their own, as practice, sometimes messing with the rules and vocabularies of those languages a bit to experiment (see: the dozens of brainfuck equivalents on esolangs.org). Writing languages is addictive; start with something simple and add complexity until you can fully express your concept.